The Curriculum Purpose, Development Process, and Design

By educational objectives, we mean explicit formulations of the ways in which students are expected to be changed by the educative process. That is, the ways in which they will change in their thinking, their feelings, and their actions.

Benjamin S. Bloom et al,

Taxonomy of Educational Objectives// (Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill, & Krathwohl, 1956, p. 26)

Purpose

The purpose of the Babson-Equal Exchange Cooperative Curriculum for Graduate Schools is to raise awareness and understanding of cooperatives among students in professional schools throughout the United States and the world. We propose that students graduating from schools of architecture, business, education, law, medicine, public health, science and engineering, and so forth should know about cooperatives both as a possible place to work and as an opportunity to start up a new venture with like-minded colleagues. We further suggest that if students come to recognize the unique value of cooperatives early in their professional careers, they may well patronize and support cooperatives and the values of cooperation throughout their lives—contributing to a world of fairness, ethical commerce, and economic democracy.[[#_ftn1|[1]](1) Of course the materials that we have assembled in this curriculum may also serve other purposes and other audiences. We have specifically selected a Creative Commons licensing arrangement to allow you to use and modify our materials for your noncommercial purposes.

| The ultimate goal, consistent with the opening quotation, is to change how students think, feel, and act about cooperatives as a place to work, to patronize, and to start in order to create both economic and social value with fellow cooperators. |

Because there are a variety of excellent, existing degree programs, courses, materials, and other resources pertaining to cooperative education, we draw from these sources rather than attempt to duplicate them. And, since new resources may be introduced at any time, we encourage you and others to post such references to the curriculum wiki site for all to share. Thus we view this curriculum as the beginning of a dynamic and collective work in progress that we hope will evolve to utilize or serve manifold and changing resources, events, and needs over time.

It is important to note that the approach and materials considered reflect almost exclusively a focus on cooperatives in the United States (including Puerto Rico), with some representation from Canada. There is little coverage of the rich heritage and vibrant activity in cooperatives in Europe, Asia, or other parts of the world except insofar as such consideration is included in some of the materials used in the curriculum, such as the readings. This narrowness is due to a decision to draw upon immediately available contacts and resources in order to produce an initial version of the curriculum, which then would be made available to the world as the beginning of a more universally inclusive approach to expanding and adapting of the curriculum.

A note on spelling: This document alternates, without preference, between the spelling “cooperative” and “co-operative,” and the abbreviation “coop” and “co-op.”

Process

Each year, Equal Exchange donates a percentage of its pre-tax profits to nonprofits that work closely aligned to its mission. In February 2010 Babson College proposed to Equal Exchange to create a curriculum on cooperatives for professional schools. Equal Exchange had previously funded the development of a curriculum for secondary schools, Win Win Solutions (Benander, 2007), and it seemed reasonable to expand curriculum development to reach higher education, as well. A copy of the proposal is in Appendix A. Equal Exchange provided a grant at half the level sought, but this was sufficient to initiate the project, the balance of funding being provided by Babson College.

The first task was to assemble an Advisory Board of respected and engaged cooperative practitioners and academics, including younger members in or recently out of graduate school. Almost all those invited joined the Board and we acknowledge them with gratitude here: Margaret Bau, Christina Clamp, Erbin Crowell, David Ellerman, José González-Torres, Mary Griffin, Melissa Hoover, Jim Johnson, Michael Leung, Margaret Lund, Rodney North, Sarah Pike, Jack Quarter, Martin van den Borre, Brian van Slyke, and Tom Webb.

The second task was to solicit suggestions for the learning objectives for the curriculum from a wide network of practitioners and academics. Appendix B includes the questionnaire emailed on 31 May 2010 to some 89 recipients, some of whom (including the US Federation of Worker Cooperatives) in turn re-sent the questionnaire to members of their respective mailing lists. On 4 June the same questionnaire was sent to an additional 49 cooperators in Puerto Rico. The relatively few responses received to date have mostly been messages of support for the effort, while some have provided substantive and very helpful responses to the questions and topics in the questionnaire. Respondents are noted in the acknowledgments section.

Interviews were conducted with the three founders of Equal Exchange as part of a research effort to collect primary data on the history of Equal Exchange for purposes of examining the life cycle of a thriving cooperative. The results of these interviews appear in the section of the curriculum dealing with the life cycle of cooperatives. Kathryn Strickland of the Food Bank of North Alabama prepared a case study that documents the planning of a cooperative to address social needs in an economically disadvantaged neighborhood.

In addition to the surveys noted above, interviews were conducted with a number of key cooperators based at apex institutions and funding agencies in Washington, DC, including Terry Lewis, former Executive Director, and Liz Bailey, Interim Executive Director of the Cooperative Development Foundation (CDF), Mary Griffin, Director of Public Policy, and Andrew McLeod, Communications Specialist, of the National Cooperative Business Association (NCBA), Lois Kitsch, National Program Director of the National Credit Union Foundation, Larry Blanchard, Public Affairs Consultant, CUNA Mutual Group, Valerie Breunig, Worldwide Foundation Executive Director of the World Council of Credit Unions, and Thomas Carter, Technical Advisor, Cooperative Development Program of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

In order to increase understanding of cooperatives, especially worker cooperatives, Equal Exchange and the United States Federation of Worker Cooperatives (USFWC) provided support to attend the week-long training program conducted by Cooperation Works (http://www.cooperationworks.coop/), “The Art and Science of Starting a Cooperative Business,” held in Madison, Wisconsin from 17 to 21 May 2010. This workshop afforded the opportunity to work closely with some 30 other aspiring practitioners, interact with presenters, including Margaret Bau, Bill Brockhouse, Brian Henehan, Margaret Lund, Audrey Malan, Bill Patrie, Sarah Pike, Lynn Pittman, Anne Reynolds, Michelle Schry, Jeff Vercauteren, and Harry Webne-Behrman, and to visit a number of working cooperatives in the area, including the Willy Street Food Co-op (http://www.willystreet.coop/), Community Pharmacy (http://www.communitypharmacy.coop/), Union Cab (http://www.unioncab.coop/), and Isthmus Engineering and Manufacturing (http://www.isthmuseng.com/). Following the workshop, site visits were made to the Food Bank of North Alabama in Huntsville, Alabama as part of the effort to document the development of a new cooperative initiative.

Additional primary research contributing to this curriculum included examining the cooperative landscape in Puerto Rico, culminating in a keynote address to an Island-wide Roundtable on Cooperative Innovation, with a focus on Youth Cooperatives, given in April 2010.

Design

In summary, the approach to curriculum development has been first, to collect recommendations for course objectives and outcomes from leading experts and practitioners in cooperatives, then to develop a proposed curriculum to achieve these objectives and outcomes, and finally to test and revise the curriculum. Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Bloom, et al., 1956; Bloom, Krathwohl, & Masia, 1964) was used as a guide to creating objectives in the following domains: Knowledge, Skills, Abilities, and Values.

Wiggins and McTighe’s Understanding by Design (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005) was used as a guide for curriculum development, particularly the approach of working backward from desired results. Wiggins and McTighe and Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick’s Evaluating Training Programs: The Four Levels (Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2006) guided the approach to evaluation.

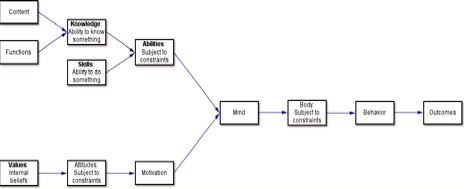

Learning domains are based on a proposed model that outlines the relationship between the domains of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives (Bloom, et al., 1956; Bloom, et al., 1964)—Knowledge, Skills, Abilities, and Values—and how they affect Behavior. The general relationships between the key elements are outlined here as follows:

1. Knowledge + Skills = Abilities (Bloom, et al., 1956, p. 38)

2. Values + Attitudes = Motivation to Act (Bloom, et al., 1964, p. 149)

3. Abilities + Motivation = Behavior [subject to constraints, such as ignorance (Simon, 1997/1945); social norms at odds with personal values (Kuran, 1995); institutional “rules of the game” (North, 2005/1990); and physical constraints or disabilities]

Figure 1: Proposed Curriculum Domain Model

The Proposed Curriculum Domain Model shows the general relationship among learning domains as they influence the mind to direct behavior, subject to constraints.

In the portion of the curriculum that deals with starting a cooperative, we focus on worker cooperatives. We assume in the case of worker cooperatives that the student in a professional graduate school may be interested in starting up a cooperative. As suc, the student is seen to be entrepreneurial. However, concerning other types of cooperatives that are not worker cooperatives, not all cooperative members are necessarily entrepreneurial, for in consumer co-ops and credit unions, for example, most members are relatively passive.

Behavior is key in entrepreneurship. In entrepreneurship education, we want to impart the knowledge, skills, abilities, and values that ultimately will ensure successful entrepreneurial behavior. Thus, in designing effective curricula we should be mindful of the behavior we seek to influence, be able to describe such behavior as learning outcomes, and then provide the learning experiences that, taken together, will promote the appropriate behavior. In actual curriculum development, this design process is not necessarily linear; it can be recursive and iterative.

Constraints refer to what we do not know (ignorance) as well as environmental (physical and social) constraints that prevent us from behaving the way we want (available infrastructure, supporting and opposing institutions, social norms, laws, threats). Conceptual contraints are treated in works that critique rational choice theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979, 2000; Simon, 1978, 1997/1945). Environmental constraints are treated in North’s institution theory (North, 2005/1990) as well as Kuran’s description of how prevailing norms inhibit true preferences (Kuran, 1995). One’s body may have physical constraints (physical disabilities), which represent not only possible obstacles to action, but also entrepreneurial opportunities to create technologies to overcome such constraints.

In reference to teaching values rather than attitudes, our proposition is that it may be more effective and sustainable to teach to and influence enduring values, and thus change attitudes, rather than to change attitudes while leaving underlying values unexamined. the proposition is that values may influenc longer-lasting behavior than attitudes. In Ajzen’s Theory of Planned Behavior (Ajzen, 1991), which focuses on attitudes, beliefs are measured as attitudes, which serve to describe and explain observed behavior. In the proposed model above, the learning of values serves to educate and influence lasting normative behavior (Rokeach, 1973).

An opportunity for conscious reflection on the role of values and preferences in a curriculum could in some cases be transformative, not only in reorienting one’s perspective (Mezirow, 1995), but also in changing how one thinks or acts (Brookfield, 2000). How such transformation is achieved can be a function of how one chooses to teach the subject matter. The educator’s aim may be to teach the course as an instrumental means by which students are able to do what is expected. Alternatively, the educator’s aim might be twofold: to teach the relevant subject matter, and also to do so in a way that provides the student with an opportunity to reflect critically on how the subject matter is to be applied, and with what consequences, for whom. Such reflection can be the purpose of individual and group exercises that allow the student to operationalize or experience what is learned. The curriculum has been designed to afford flexibility in terms of the individual educator’s aim.

The first step in design has been to assemble a list of the proposed educational objectives and to formulate them in the categories of learning objectives noted above. Then, beginning with a semester-long format of 14 2.5-hour classes meeting once a week, a teaching guide and syllabus containing sequenced readings, exercises, and assignments to meet most, if not all objectives, is provided. The teaching guide consists of a class-by-class presentation of material to be presented by the teacher to the students. The first seven classes are considered core material for the semester-long course. The subsequent classes may be selected by the teacher and ordered in any way seen appropriate. A teacher may also decide to combine material from two or more classes for presentation in a single class. The aim has been to provide choice and options.

A 7-class, half-course addresses a subset of the total learning objectives. Again, teachers should view this only as a guide and feel free to construct their own short courses from the material. And finally a two-part modular workshop is offered, with each module consisting of an intensive four-hour treatment of the material. The first module is introductory in nature, and the second, optional module is designed for students who wish to explore actually starting up a cooperative. Each class in the curriculum is described by a set of considerations beginning with the class subject title, which introduces a brief overview of the topic.

Note that references to a syllabus imply that a sequence of specific classes will be provided; however, it is up to the teacher to construct an actually syllabus by using the material provided in the relevant class section(s) that are described as follows.

Subject title: The overview is about 5-10 pages of double-spaced text. This description provides the teacher with enough information to be able to assemble class notes for a lecture and discussion.

Learning objectives: The learning objectives, which open each topic, indicate exactly what should be imparted in the class, and typically takes the form of an enumerated list of objectives starting with “To learn ...”

Background reading: This section indicates the recommended readings meant for the teacher’s reference.

Required reading: The required reading lists the readings for the student.

Optional reading: The optional reading section lists additional but optional readings for the student.

Exercises: The exercises section describes any in-class or out-of-class individual or group exercises that will help students achieve the learning objectives.

Many of the class guides were written by content experts—academics or practitioners who represent leading authorities in the subject matter addressed in the section. Teachers are encouraged to consult and draw from other sources, some of which are listed in the background, required, and optional reading sections of the guide.

In addition to the teaching guide and syllabi, two original case studies are provided, one on Carpet One; the other, a research case study, on the Pulaski Pike Cooperative Market. Using the distinction noted by Yin (2003, 2009), the research case study is different from the popular teaching case studies written to encourage class discussions, principally in business schools and increasingly in other graduate professional schools. Because some readers may not be familiar with the distinction between teaching and research case studies, we draw from Yin to clarify (2003):

For teaching purposes, a case study need not contain a complete or accurate rendition of actual events; rather, its purpose is to establish a framework for discussion and debate among students. ... Teaching case studies need not be concerned with the rigorous and fair presentation of empirical data; research case studies need to do exactly that. (p. 2)

In teaching, case study materials may be deliberately altered to demonstrate a particular point more effectively (e.g., Stein, 1952). In research, any such step would be strictly forbidden. (p. 10)

While we recognize a role for teaching case studies in the curriculum, we are primarily concerned here with an accurate, research-based description that will also serve as a basis for educational class discussion.

When drawing from the Curriculum materials offered herein, the teacher is advised to reflect on how multiple dimensions of understanding can be imparted to students. These are well articulated by Wiggins and McTighe (2005):

When we truly understand, we

· Can explain—via generalizations or principles, providing justified and systematic accounts of phenomena, facts, and data; make insightful connections and provide illuminating examples or illustrations.

· Can interpret—tell meaningful stories; offer apt translations; provide a revealing historical or personal dimension to ideas and events; make the object of understanding personal or accessible through images, anecdotes, analogies, and models.

· Can apply—effectively use and adapt what we know in diverse and real contexts—we can “do” the subject.

· Have perspective—see and hear points of view through critical eyes and ears; see the big picture.

· Can empathize—find value in what others might find odd, alien, or implausible; perceive sensitivity on the basis of prior direct experience.

· Have self-knowledge—show metacognitive awareness; perceive the personal style, prejudices, projections, and habits of mind that both shape and impede our own understanding; are aware of what we do not understand; reflect on the meaning of learning and experience. (p. 84)

The Curriculum offered here is no substitute for the teacher who must deliver the course. How teachers may choose to address the above six dimensions of understanding is best left to their teaching acumen.

To the greatest extent practicable, and with appropriate permissions, we have used or drawn from existing materials. Where necessary we have produced new, original contributions. Finally, as previously noted, all materials offered here are, unless otherwise noted, covered by the Creative Commons license terms that allow free, non-commercial use and modification.

Standard learning objectives

While each component of the Curriculum has its own learning objectives, there are several standard learning objectives that have been compiled from recommendations by the Curriculum Advisory Board that all students should achieve. Thus, by the end of any configuration of a cooperative course based on this curriculum, every student should be able to:

1. Explain why the cooperative model of organization has emerged.

2. Name the seven cooperative principles.

3. Provide a real example of each type of cooperative.

4. Describe the key differences between cooperatives (either for-profit or nonprofit) and conventional for-profit companies, ESOPs, and nonprofit organizations.

5. Explain why cooperatives are more or less appropriate in different industries.

6. Explain the value and challenges of democratic control in cooperatives, versus concentrated control in traditional, hierarchical organizations.

7. Describe the life cycle of a cooperative and the most critical challenges faced at each level in the cycle.

8. Explain why or why not the student would prefer to work in a cooperative or other type of organization.

Additional considerations are addressed in the Evaluation section in Curricular Options below.

1. The vision of Equal Exchange is, in part, to set an example as a world leader in fairness, ethical commerce, and economic democracy. See http://www.equalexchange.coop/our-co-op, cited 30 January 2011.